By Iswat Ishola and Angel Asifat

Picture this: it’s your wedding day, supposedly the happiest day of your life. Everything is going exactly as you planned in your dreams. Then suddenly, there’s a gunshot from afar! The sound prompts your Nigerian survival instincts; you run with your newly wedded spouse. Just as you take your first step, you hear another pow! But this time the sound is closer and louder. Blood splatters everywhere as you watch your new spouse drop to the ground in a blatant succumb to death. This is what viewers were made to experience in the action-thriller, The Herd.

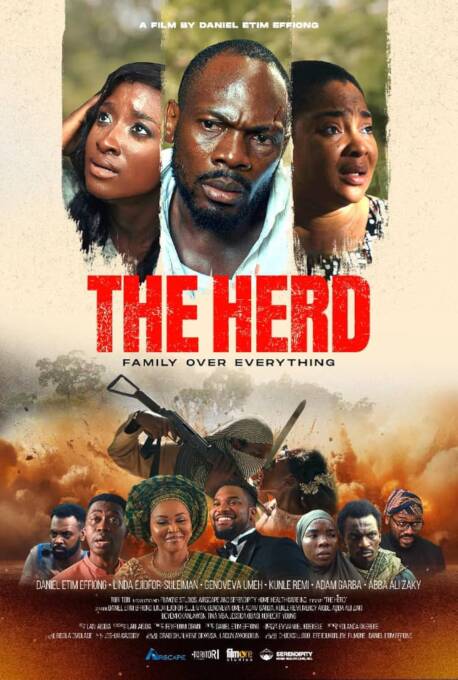

The Herd, directed by Daniel Etim-Effiong and currently streaming on Netflix, is a gripping film that reflects the disturbing reality of kidnapping, terrorism, and insecurity in Nigeria with emotional depth and social relevance

It opens with the joyful wedding of Fola (Kunle Remi) and Derin (Genovova Umeh), a moment filled with hope and celebration. Fola is killed instantly, and Derin, a newlywed who should be celebrating the beginning of her married life, is left dumbfounded, heartbroken, and traumatized. The film captures her shock and grief authentically, portraying how quickly joy can turn into despair in the face of violence. From this very opening, viewers experience the harrowing intensity of terror and the personal cost of insecurity.

Alongside Derin’s tragedy is Gosi’s (Daniel Etim-Effiong) intense struggle. Already burdened with the stress of his wife’s cancer and desperate to find funds for her treatment, he is now forced to confront a life-threatening kidnapping scenario. His resourcefulness, courage, and determination to survive while protecting Derin highlight the human instinct to fight for survival even under extreme pressure. Gosi becomes the emotional anchor for viewers, demonstrating both vulnerability and resilience in a world violently upended.

The Herd also paints a heartbreaking picture of families left behind. Adanma (Linda Ejiofor-Suleiman), despite her illness, scrambles desperately to gather ransom for her kidnapped husband. Her plight is made even more complex by the caste system, as she is an Osu and her in-laws never wanted her to marry their son. Under pressure, she is forced to sign an agreement to divorce him in exchange for receiving the ransom money, adding another layer of social injustice to her already overwhelming struggle.

ALSO READ

On the other hand, Habiba (Amar Umar), once a victim herself, is now part of the gang, illustrating how trauma can distort a person’s identity and choices. These layered storylines humanize the crisis and show that everyone affected carries a different pain. The movie ultimately passes on a big message, showing terrorism from the point of view of victims and their families — an angle that deeply resonates with viewers.

The bandit group is portrayed with disturbing realism, complete with internal conflicts and cultural diversity — members from Yoruba, Hausa, and Igbo backgrounds — reflecting how widespread these criminal networks can be. The leadership feud between Halil and Sheikh adds tension, though this thread could have been explored more deeply. At times, one could even feel sympathy for the bandit leader, as their actions are framed as money-driven rather than purely malicious, which underplays the real-life wickedness of such crimes. Nonetheless, it remains the closest cinematic depiction we currently have of terrorism and insurgency in Nigeria.

A major strength of the film is its portrayal of the police response. Gabar leads the rescue team with determination, supported by officers like Niji and others who work tirelessly to locate the victims. Their coordinated efforts highlight heroism and raise an important question: Is this the same level of urgency and commitment we see in real-life police responses? The film leaves this reflection to the audience, balancing cinematic drama with social commentary.

While emotionally powerful, the film occasionally struggles with pacing and narrative flow. Some scenes — especially the long trek through the forest — feel repetitive, and sudden plot points, such as Mama Rainbow’s role as a community informant or the involvement of a corrupt religious leader dealing in human parts, are introduced without full development. The movie also hints that victims with influential connections are more likely to be rescued, but it does not fully explore the fate of others, leaving some unanswered questions.

Still, the performances, including Gosi’s emotional turmoil and Derin’s grief, hold the film together. The Herd succeeds in portraying the chaos, trauma, and social tension surrounding kidnappings, while also showing the suffering of victims, the desperation of families, the brutality of the bandits, and the complexities of survival.

The Herd is bold, timely, and emotionally resonant, leaving viewers with a deeper understanding of a crisis that continues to shape daily life in Nigeria. Right now, it is the closest description we have to the actual nature of terrorism and insurgency in Nigeria.

Iswat Ishola and Angel Asifat are content writer interns at News Round The Clock.